Meta’s policy changes and why they don’t help

By: Vartan Arakelian

We live in a world where the abundance of online material and social media users understandably results in large amounts of misinformation that are more accessible and disseminated faster than ever. The solution to this societal issue, according to Mark Zuckerberg, is to abandon Meta’s nearly decade-old fact-checking system and instead rely on a “Community Notes” program similar to the one already utilized by X. Meta expressed concern that its third-party fact-checkers were prone to injecting their own biases in content moderation, leading to excessive censorship. The company wrote in a statement, “Experts, like everyone else, have their own biases and perspectives… Over time we ended up with too much content being fact checked that people would understand to be legitimate political speech and debate.” Zuckerberg and other Meta decision-makers hope to reduce bias in fact-checking and allow more free speech through their new system, by which contributing users write and rate “Community Notes” without any input from Meta itself. The “Community Notes” approach is not viable, as it is Meta’s responsibility and not its user’s to ensure that the information spread on its platforms is either factually accurate or supported by appropriate context. Fact-checker bias should be minimized, but it is counterproductive to do so by discontinuing the valuable fact-checking system.

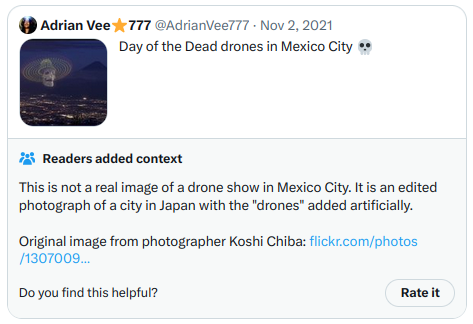

Meta’s fact-checking system is trusted by average users and is therefore more effective in reducing misinformation than “Community Notes.” In the pre-existing system, which will continue to be used outside the US in part due to stricter international laws, the company detects potentially misleading posts and sends them to third-party fact-checkers, who then review the content and set an accuracy rating. Posts that fact-checkers determine to be false experience limited circulation and receive warning labels linking to an original source proving their inaccuracy. According to Scientific American, “a 2019 meta-analysis of the effectiveness of fact-checking in more than 20,000 people found a ‘significantly positive overall influence on political beliefs’” when it comes to reducing “misperceptions about false claims.” A survey Meta itself conducted several years ago concluded that 74% of its users had positive opinions about its fact-checking system. Additionally, while fact-checkers might indeed let their biases show through the decisions they make, social media users are often just as biased, if not more. As recently demonstrated by the spread of misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic, not every public consensus is factually correct, especially with regard to newly developing events and scientific breakthroughs. For this reason, expert verification is invaluable for preserving the truth.

Furthermore, the “Community Notes” concept works significantly slower than the preexisting system and puts into question its viability as a fact-checking system. First of all, users will likely be slower than dedicated fact-checkers in identifying misleading information, as Scientific American reports that an analysis of X community notes found that they were added too late on problematic posts to have a significant effect in mitigating the spread of false information. After the notes have been written, users then have to rate the bias level of those notes for them to be widely shown; this adds a layer of unnecessary complexity that reduces the system’s efficiency. The fact that users from both sides of the political spectrum must approve of the community notes means that some misleading and partisan posts might not get those notes shown at all. Rumors and false claims spread rapidly, so it is important to provide factual context to misleading posts as soon as possible to limit their potential harm to society. The “Community Notes” system prioritizes “free speech” over the efficiency of fact-checking. The latter should be more important in this context, especially since, under the pre-existing system, fact-checkers did not completely obstruct free speech but rather provide factual context to posts.

While reliance on third-party fact-checkers has its flaws, it is a better alternative than letting users perpetuate harmful misinformation. This is because mitigating the spread of false information is very challenging once it already threatens the legitimacy of the truth in the public’s eyes. To reduce bias when censoring posts determined by fact-checkers to be misleading, Meta could allow its users to provide feedback if they believe a post has been incorrectly identified as false. This would maintain the efficiency of the fact-checking process concerning initial identification and suppression of misinformation while giving users a say in correcting unnecessary censorship. “Community Notes” and the fact-checking system are also not mutually exclusive. Meta could allow users to write context notes themselves while preserving its collaboration with fact-checkers as a tool for quickly limiting the spread of viral and misleading content. At the end of the day, getting rid of fact-checkers is not Meta’s best solution. Instead, the company should strive to maintain public trust in the factual correctness of its platforms at a time when believable but false information can exist anywhere and everywhere. “Free speech” does not mean that decision-makers can afford to sit back and watch as society is misled by enticing claims that turn out to be objectively untrue.

Leave a Reply