…just not in the way you think

By: Sophia Stafford

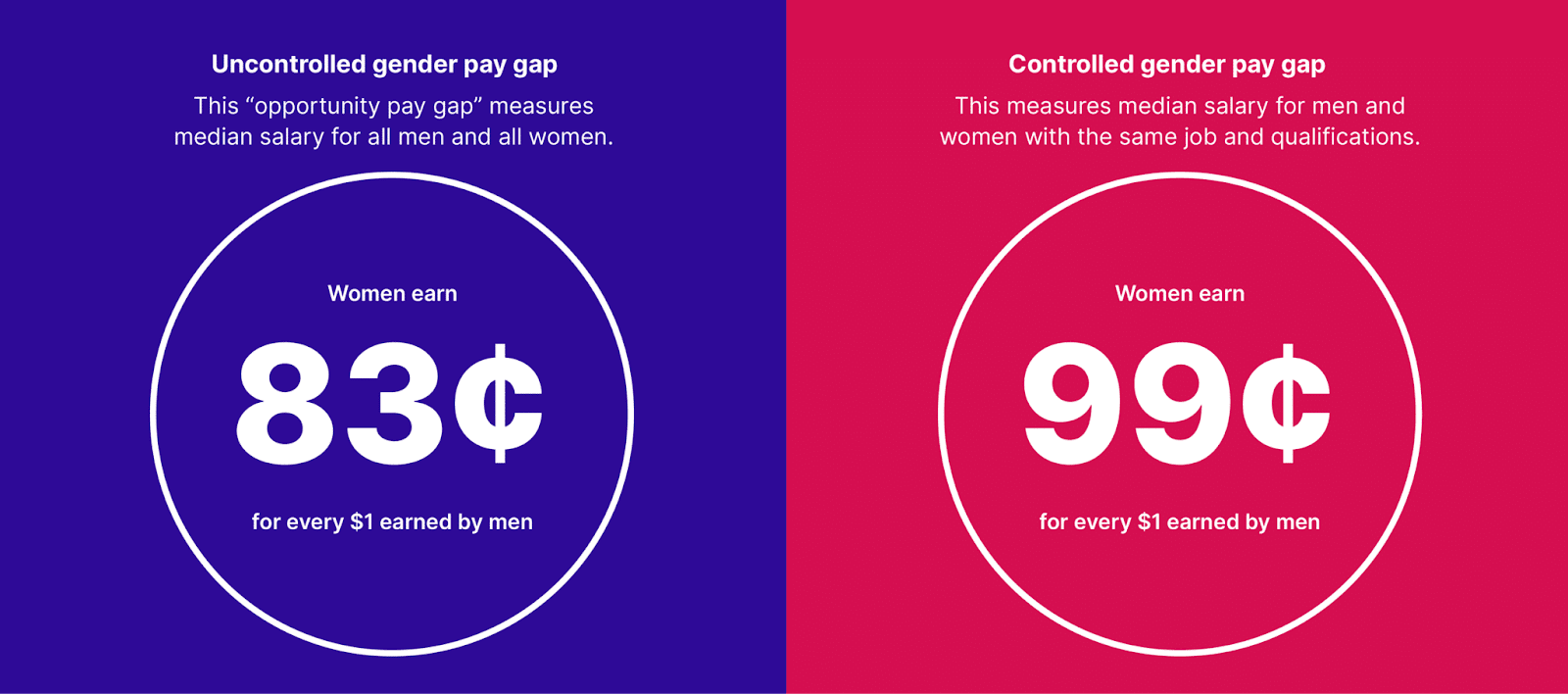

“Multivariate analysis of the pay gap indicates that it doesn’t exist,” declares Professor Jordan Peterson in a 2018 interview with Channel 4 News. Peterson is correct… technically. There are two ways to measure the gender pay gap: controlled and uncontrolled. Controlling for the factors of hours worked, years of experience, job level, and industry, the gender pay gap is virtually nonexistent. Globally, the controlled gender pay gap is only 1%. For every dollar earned by a man, a woman makes 99 cents. However, the controlled pay gap does not accurately represent our world, as the odds are stacked against women for every factor in the analysis. Men tend to have more experience and work more hours because they usually are not the primary caregivers of their children. Men are more likely to get promoted to a higher job level. Men dominate high-paying industries.

The other way to measure the gender pay gap is the uncontrolled gap: the ratio between the median salary of all full-time employed women and the median salary of all full-time employed men. Currently, these studies show that women earn an average of 17% less than men. In other words, for every dollar a man earns, a woman makes 83 cents. Now, Peterson’s statement doesn’t seem as compelling. Although men and women with the same position have relatively equal salaries, this observation hides the additional challenges women face in achieving these roles because the controlled gender pay gap does not reflect the social and systemic issues that limit women’s careers.

Let’s begin by tracking the gender pay gap through men’s and women’s careers. Starting just out of university, men and women with the same qualifications have relatively equal salaries. Between the ages of 20 and 29, the uncontrolled pay gap is 87 cents to the dollar, and the controlled gap is nonexistent: controlling for various factors, men and women make the same amount of money. However, that gap widens considerably as their careers progress. Between the ages of 30 and 44, the uncontrolled gender pay gap widens to 82 cents to the dollar and the controlled gender pay gap widens to 98 cents to the dollar. The reason for this is fairly straightforward: this is the point in workers’ lives where they become parents.

Parenthood impacts men’s and women’s careers very differently. In our patriarchal society, the father is expected to provide for his family, and the mother is expected to take care of the children. This expectation shapes our reality. Around 70% of primary caregivers are women, so when a mother needs to spend more time at home with her children, she can’t spend that time at work. Around 85% of women leave the full-time workforce within 3 years of having their first child.

When women leave the workforce, even if they return years later, they put themselves at a severe disadvantage. Salary is based almost purely on years of experience and job level. Because women tend to spend less time at work after having children, they fall years behind on the pay and promotion ladder compared to their male equivalents due to stark differences in experience. Men are over 14% more likely to be promoted within a company than women.

The lack of women in leadership positions is also influential on a societal level. Many high-paying jobs, like corporate executives, investment bankers, and law firm partners involve multiple promotion rounds. The higher up you rise within a company, the higher your salary. However, in these high-paying industries, there are often very few women in the top leadership positions because they need to make it through many, many rounds of promotions. So, the best chance a woman has at a top leadership position is in an occupation where there are few promotions. This is why we see a lot of women going into education, social services, and nursing, fields where around 40% of senior management roles are filled by women. In these industries, women have higher chances of achieving leadership roles than in male-dominated industries, but the jobs are generally lower paying.

This cycle affects the next generation as well. If you are a young girl deciding what you want to be when you grow up, seeing females in leadership positions can shape your ambitions. This can be seen as early as high school. Last year, girls comprised around 66% of total test takers on the AP Psychology exam and 62% on the AP English Language exam. On the other hand, girls only comprised around 23% of total test takers on the AP Physics C exam and 25% on the AP Computer Science exam. We see girls preparing for industries where there is a higher number of women in leadership positions. In comparison, boys tend to prepare for higher-paying sectors, where there are far more men in positions of power.

All of these elements come together to create a destructive dynamic. By acting as the primary caregiver for children, women must spend more time at home, limiting their opportunities to work frequently and advance in their careers. The lack of female representation in high-power positions means that young girls are not encouraged to pursue high-paying industries. Peterson’s “multivariate analysis” shows that when women and men are given the same opportunity and the same job they perform equally well. But that analysis hides the fact that women, often, do not get those opportunities.

https://manoa.hawaii.edu/careercenter/women-and-the-gender-pay-gap/ 2

The controlled gender pay gap does not reflect the social and systemic issues that limit women’s careers.